A summary of my workshop from the ESOL SIG Showcase on 10 April 2025 at IATEFL 2025:

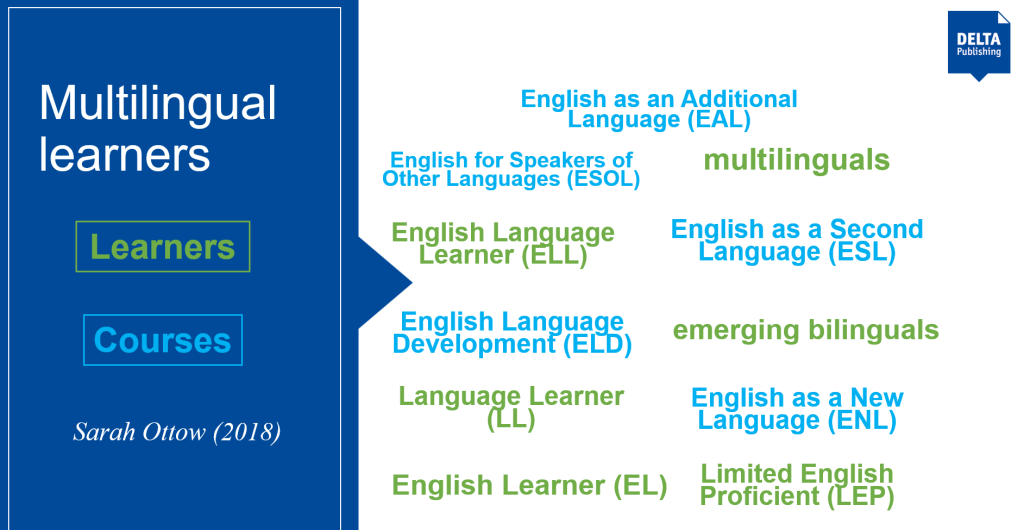

Who are multilingual learners?

We started the session by discussing who multilingual learners are. We looked at all the different labels and designations that are used globally (Sarah Ottow, 2018). As you can see in the image, the green terms are used to refer to the learners, while the blue ones are the courses designed for them.

If you feel overwhelmed by the many names, you are not alone! It’s quite telling just how much we want to define the learners we work with. But why is that?

The DfE (2019) defines EAL learners as anyone who has been ‘exposed to a language at home that is known or believed to be other than English’. I personally find this definition unhelpful and too vague. It does not take fluency in English into consideration, which is one of the most important markers used in international schools. In my context, I need to be as specific as I can be when referring to the learners I am responsible for because about 95% of our school population is multilingual. This is the norm, not the exception! Not to mention that students who graduate our EAL programme are still learners of English just at a higher stage of their language development. For practicality’s sake, we use the term ‘EAL learners’ to refer to the learners who receive regular EAL support.

One of the dangers of such labels is that it’s easy to assume that every EAL learner is the same. This couldn’t be further from the truth. EAL learners are a heterogeneous group with diverse needs. Of course, there are things they all share:

- They are often unfamiliar with not just the language of instruction, its script, its sounds, etc. but with the context and expectations of their new schools and the wider community. This is especially true if they have recently arrived in the country.

- They aren’t fluent in English, which limits their chances of expressing their thoughts and feelings. And in my context, they are often New to English, meaning that they aren’t able to communicate in English even their most basic needs. This makes supporting them all the more important, albeit challenging.

- Their Funds of Knowledge (FOK) (Moll et all., 1992) exist in a different language – everything they have learned before is suddenly inaccessible to them. This might manifest as a loss of motivation, unwanted behaviour, frustration, etc. Just imagine being an A* student who suddenly can’t access even the most basic content. I’d be frustrated too!

- They have the incredibly challenging task of learning the language of instruction, while learning content through that language. And to be able to succeed, they also need to learn the language of learning.

Linguistic support

Practical strategies

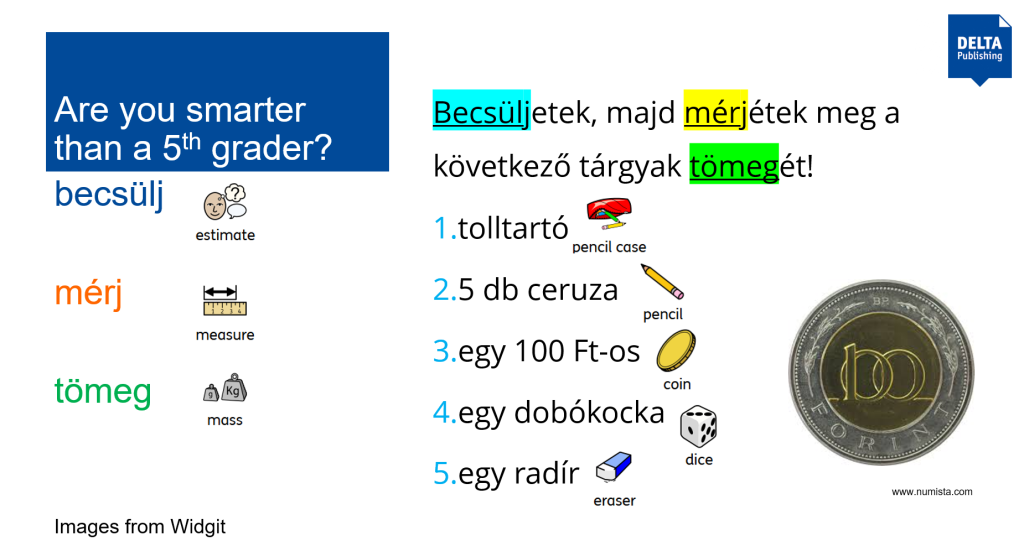

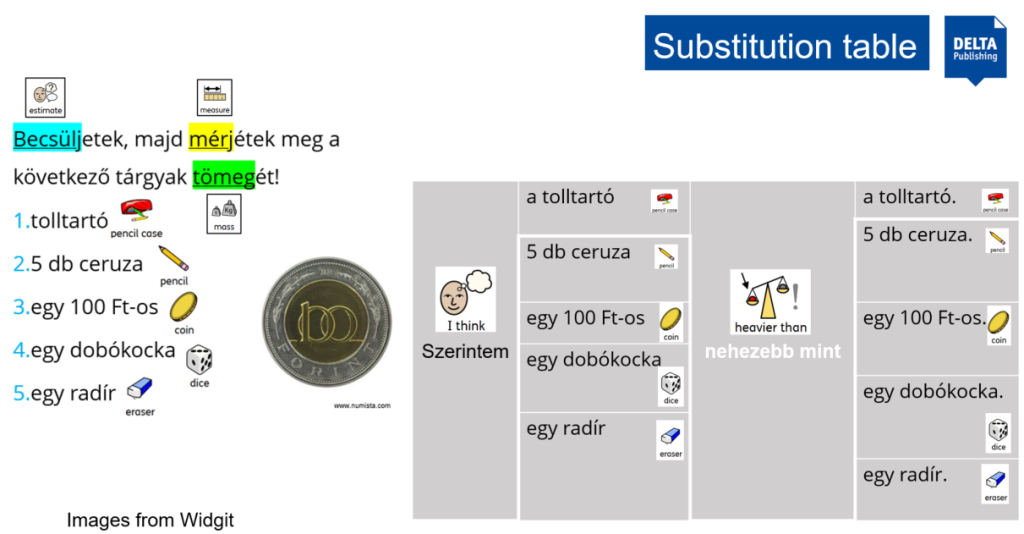

During the workshop, participants experienced what it’s like to be an EAL learner when they were presented with a 5th-grade mathematics problem in Hungarian. Through this example, we looked at different ways to provide linguistic support. We discussed:

- the importance of glossaries and visual support. As you can see, I used images from Widgit Online, but hand-drawn images, Google Images, or other free websites are just as helpful.

- tiers of vocabulary (Beck et al., 2013).

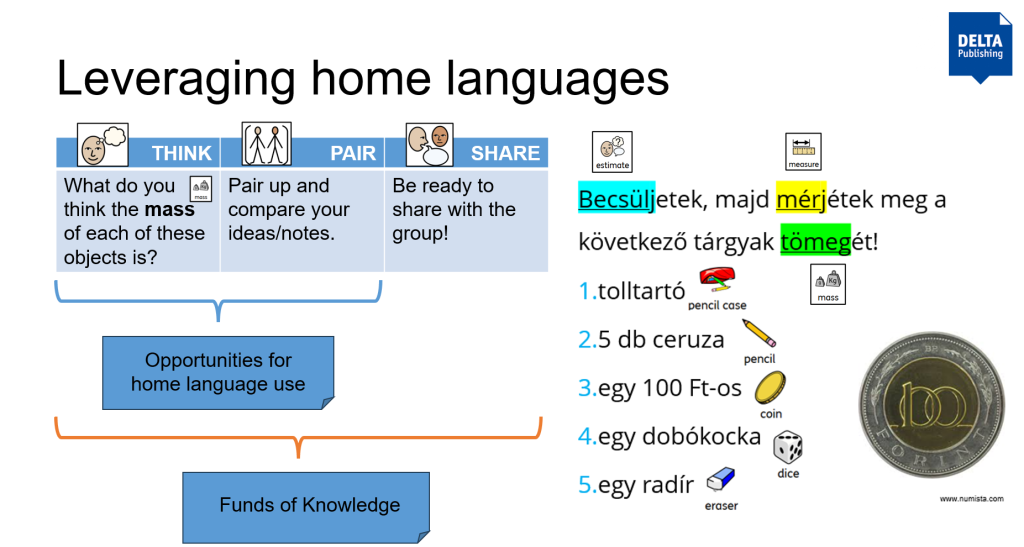

- how to make Think-Pair-Share more EAL friendly.

- why all lessons need dual objectives where content and language aims are made explicit.

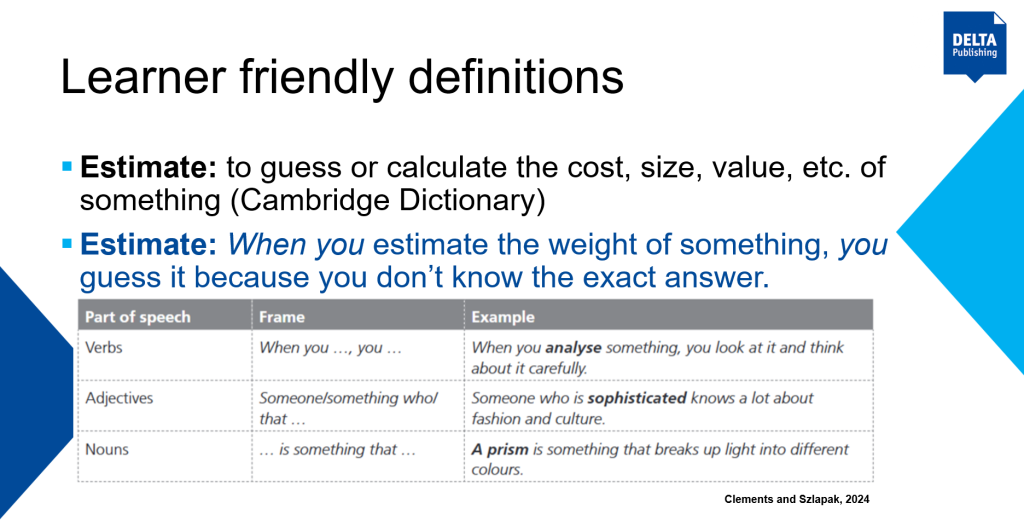

- how to teach our learners to create learner-friendly definitions. This is a great strategy to exploit the content of a lesson for language instruction.

- the versatility of substitution tables. Substitution tables are great resources that can help us balance content and language. If the content challenge is high, e.g. the earlier maths example, we should provide more language scaffolds.

Home language research

As you can see in the examples, the use of home languages featured heavily in this workshop. There is good reason for that. Home language research tells us that there are tremendous benefits to L1 use: Teachers’ use of a learner’s L1 in class has been found to contribute to learners’ cognitive growth, as well as to their emotional, social, and cultural capital (Oliveira & Jones, 2023) or knowledge base. The use of L1 involves a value-based judgment “in which teachers have a moral obligation to use the learners’ own language judiciously in order to recognise learners as individuals, to communicate respect and concern, and to create a positive affective environment for learning” (Edstrom, 2006).

Attitude matters: the extent to which own-language use occurs in a class depends on the attitudes of teachers and learners towards its legitimacy and value in the classroom, and many studies report a sense of guilt among teachers when learners’ own languages are used in class (e.g. Macaro, 2009; Butzkamm and Caldwell, 2009; Littlewood and Yu, 2011). That said, several studies have uncovered positive attitudes, particularly as a way of reducing learners’ anxiety and creating a humanistic classroom (Harbord, 1992; Rolin-Ianziti and Varshney, 2008; Brooks-Lewis 2009; Littlewood and Yu, 2011). Use of the learners’ own language has been found to be prevalent within classrooms, even in contexts where it is ostensibly discouraged (see also, for example, Kim and Elder, 2005). Many teachers recognise the importance of English as the predominant, but not necessarily the only language in the classroom.

Conclusion

Supporting multilingual learners in content lessons is a dynamic process. EAL specialists are constantly responding to what the learners need by trying to maintain the balance of content vs language challenge. This scale is an apt image to represent what we do. To allow access to the curriculum, EAL specialists support learners to be able to process the language and the content at the same time. To mitigate the cognitive load:

- when the content challenge is high, we need to find ways to scaffold the language; and

- when the content is familiar, we exploit the context for language instruction.

Resources

You can find a PDF copy of the slides from the workshop here.

The strategies presented in the workshop come from this book.

Read more about in-class support in practice here.

References

Clements, P. and Szlapak, A. (2024). Supporting EAL Learners: Strategies for Inclusion, DELTA

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms. In Theory Into Practice, (Vol. 31(2), pp. 132-141)

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. Guilford Press

De Oliveira, L. C., & Jones, L. (2023). Teaching Young Multilingual Learners: Key Issues and New Insights. Cambridge University Press

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. In Educational researcher, (Vol. 41(3), pp. 93-97)

Edstrom, Anne. (2006). L1 Use in the L2 Classroom: One Teacher’s Self-Evaluation. Canadian Modern Language Review