I often hear my students say how anxious they are about Assessment Week, which is usually the last but one week of the term in my school. I find that funny, to be honest, because they are assessed all day, every day. The only difference when it comes to Assessment Week is that it’s been given a label. So, I guess, it’s the label that’s scary more than anything.

I always point this out to my students because it’s important they understand that assessments aren’t bad. Formative assessments are the backbones of teaching. They provide teachers with valuable information about what the students know and can do independently and what they need more help with. They also help the learners figure out how to get better. Summative assessments can be just as beneficial, although, by nature, they tend to be more rigorous as performance gets converted into some kind of a grade. Again, it’s essential that students realise that assessments are a big part of their everyday lives so that the anxiety can be channeled into focus and concentration instead. At the end of the day, if you have done something a hundred times, you are less likely to panic, right?

Online assessments

My experience of online assessments has been a bit like a roller coaster and I get the feeling that my students feel the same way. When we first started teaching online my instinct was to stick to what I knew so I tried to transfer the paper and pencil tests onto an online format. Of course, that didn’t work too well. There were many problems including monitoring the tests, which were much more difficult online than in a face-to-face classroom. I couldn’t be sure if the results reflected the truth about my students’ knowledge and capabilities. I also couldn’t be sure I was being entirely fair to them. We were all new to studying online, not just me. The students felt awkward in so many ways and online assessments just seemed to have added an extra layer of anxiety.

Online schooling changed the context of assessments. Suddenly we weren’t able to resort to exam conditions as easily as before. The new normal meant that the teaching community had to come to terms with the fact that students had help and there was very little anybody could do about it. Help came in different shapes and sizes. Some learners relied on their parents, their siblings, their friends, and of course Google. But is help a bad thing?

Open book assessments

I panicked at first. How was I supposed to know what they know? How can I make sure they don’t cheat? And then I realised I need to embrace the help they are getting because I can’t fight it. So I started doing open-book assessments, which have had a great washback on my courses and teaching. Open book assessments are exactly what the name suggests. I let my students use help, be it books, notebooks, Jamboards, Google or dictionaries. I have found that these assessments work much better because

- they encourage engagement. Students become more involved not only in revision but also in the whole process of assessment. This leads to an atmosphere where they are more likely to take risks and try over and over again.

- finding the answers to questions becomes part of the learning process. By allowing them to use help, they are more likely to focus on other aspects of language use such as accuracy or appropriacy.

- cheating becomes a non-issue. Let’s face it, as long as our learners are in their homes and not in our classrooms, there is very little we can do to stop them from using help during an assessment. However, by allowing them to do so takes cheating out of the equation.

Here’s how I run open book assessments:

- I turn lower-stakes assessments into challenges. By simply renaming a test and calling it a challenge, motivation rises.

- Of course, they still get graded and of course, they know what for. I always share my grading criteria with them before any assessment so that there are no surprises. Once learners know what they need to do and what they will be graded on, they become less anxious.

- I sometimes make the passing grade 100%. I mean, if you’re allowed to use help, then I expect you to get everything absolutely correct. At times I even allow students to take these tests as many times as they want to, but I expect them to get everything correct eventually.

- I allow learners to make their own cheat sheets. For obvious reasons, this works better in face-to-face lessons than online. I got this idea from my high school Physics teacher, who would only allow us to take a pencil, an eraser, a calculator, and an A4 size piece of paper into any assessment. We were allowed to write as much as we wanted on that piece of paper prior to the test and we were free to use our notes while we were working out the answers. Now, I was never any good at Sciences but by putting effort into making my cheat sheets I always managed to revise enough to pass. So, I let my student bring a cheat sheet too because I find that those who put effort into making them have spent valuable time preparing and it pays off, both for them and for me.

Some guidelines for open book assessments

- By making the tasks as similar to real life as possible we can ensure that we are assessing the application of knowledge. For instance, instead of just asking students to define a word or translate it, ask them to use it in a sentence about themselves. If they manage to use it appropriately, it won’t matter whether they have had to look it up in a dictionary first.

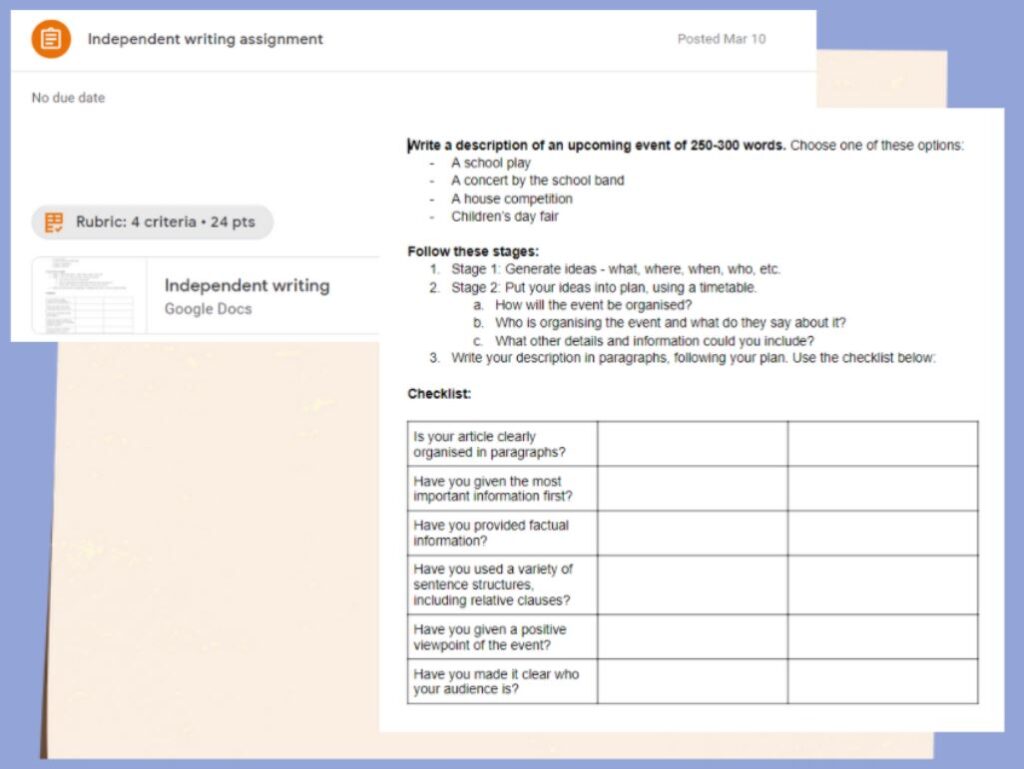

- When setting a writing assessment online, make sure that the task is so specific or personalised that there is very little help students can get from the internet. In the example below I gave specific instructions as to what I wanted to see in the writing, which meant they weren’t able to just copy-paste from a website. I also made the assessment criteria specific to this particular task, which again meant that even if they use help (e.g. Google Translate) they will have to make those sentences fit their context.

- Online quizzes can also be turned into an open-book assessment. I use Quizizz quite a lot because of how easy it is to integrate it with Google Classroom. I usually make the students take the test in a live lesson with a time limit. However, I then make the same test available for everyone so that they can take their time going through the same questions with whatever help they want to use. They are also encouraged to do the test several times or until they get 100%.

Conclusion

Assessments have been and will always be important factors in education and each method has its merits. Open-book assessments are no exceptions. I have found them to be immensely beneficial because they lower students’ affective filters, get them much more involved in the whole process and allow me to see to what extent the learners are able to apply their knowledge.